In the first of five blogs on megatrends, Rob Noble considers our changing world and what the shifting demographics mean for security globally and at home

But what of this increasingly complex environment facing organisations, and the commensurate changes it drives from security need? A US Department of Defence term of great utility in setting the context is VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity), a term coined following the collapse of the Warsaw Pact when threat seen previously as normal came to an end and most importantly it was not replaced by anything as tangible.

Much work has been done to put challenges and trends in context, and seek to identify the opportunities and threats they represent as we deal with this VUCA world. Major consultancy organisations such as Deloitte, EY, KPMG, McKinsey&Company, and PWC amongst others describe megatrends and their implications for economies and societies; as well as the opportunities they create. In our capacity as a risk mitigator and provider of security solutions we offer thoughts and observations.

Over coming weeks, we will consider five megatrends: ‘Shifting Demographics’, ‘Technology Advances’, ‘Global Power Shift’, ‘Resource Stress and Security’, and ‘Urbanization’. We do not seek to answer all of the questions, but perhaps we can stimulate thoughts around these topics.

MEGATREND 1: SHIFTING DEMOGRAPHICS

So where do Governments spend their money… which priority is the priority?

Our world is changing. Shifting demographics and the changing make up of populations internationally has, and will continue to, influence governmental budgets and priorities. In developed economies, greater life-expectancy and higher average ages raise our expectations from health provision, and grow the percentage of the population receiving the state pension and requiring funded care.

Our world is changing. Shifting demographics and the changing make up of populations internationally has, and will continue to, influence governmental budgets and priorities. In developed economies, greater life-expectancy and higher average ages raise our expectations from health provision, and grow the percentage of the population receiving the state pension and requiring funded care.

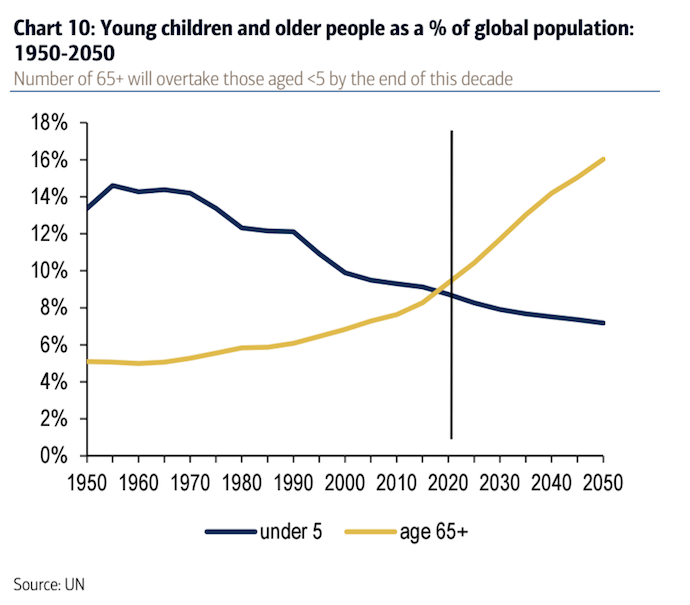

‘The world is about to see a mind-blowing demographic situation that will be a first in human history: There are about to be more elderly people than young children. Just before 2020, adults aged 65 and over will begin to outnumber children under the age of 5 among the global population, according to a report from the US Census Bureau.’ – World Economic Forum[i]

In addition to the natural shift in demographics there are the changes that result from world economics and events. In normal times people routinely move between geographies based upon better prospects for work in other countries or the opportunity to flee political repression; and with state control, the numbers are likely small and unlikely to destabilise either economy or security. Events of the last few years in Africa and the Middle East have however resulted in moves of people in numbers that have, and continue to have the potential to, negatively impact security in Europe. Health and social security budgets struggle with increased numbers to provide for, which can cause disquiet in communities or potential nationalist kickback; and defence and security budgets having to respond may invest in extensive and expensive physical measures, or costly intelligence and intervention measures.

The range of pressures facing our politicians broadens and managing the opinions of the minority view as well as the majority in any local or national election is critical. Funds available for defence and security come under greater competition and scrutiny, and some areas of risk may require to remain just that with only the highest of domestic priorities being addressed.

‘The British Army, at 80,000, is the smallest it has been since Napoleonic times’

The challenges and changes to defence and security spending and reduction in the size of militaries and police forces can be seen as a response to the pressure on national budgetary spending. The British Army at 80,000 is the smallest it has been since Napoleonic times, and the number of Police officers in the UK is at its lowest for over a decade at 200,000. Defence spending began a long decline after World War 2, from around 50% it reduced to 7 % GDP in 1959, 6 % in 1968, below 5 % in 1987, and then held at about 4 % in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Since then defence spending reduced further below 3 percent after 1997 and has continued to do so ever since to a predicted 2.3 % of GDP in 2020. Correspondingly Public spending has risen from a steady 35% in the post war years to around 40% on average and highs of 45%; with the spend on health growing in the same period from 4% to 8%, welfare 3% to 6%, and pensions from 5% to 15%.

So how might poverty be an indicator of risk to guide defence and security spending?

Suffering the impact of poverty and joining the ranks of the dispossessed who lack aspiration and expectation in life is also to be vulnerable to becoming involved in crime or recruitment to the most radical of views or actions. This is most worrying in situations where this group is made up of young males, who do not believe they have any potential within the system, and see signs of how a small elite in their country is doing very well in spite of the general situation. With limited options, they may follow an alternative path to what they believe is fulfilment. The recruitment machine of ISIS for example is said to have offered $500 a month to potential fighters.

In the developing world where state aid is not available, the percentage of the population considered poor or living in poverty, unable to achieve education or find employment continues to grow. The latest World Bank Africa Poverty Report states that the share of Africans who are poor fell from 56% in 1990 to 43% in 2012 however, because of population growth many more people are poor, the report says. The most optimistic scenario shows about 330 million poor in 2012, up from about 280 million in 1990; and poverty reduction has been slowest in fragile countries, and rural areas remain much poorer, although the urban-rural gap has narrowed. Globally, according to the most recent World Bank estimates, in 2013, 10.7 percent of the world’s population lived on less than US$1.90 a day, compared to 12.4 percent in 2012. Which is down from 35 percent in 1990. This means that, in 2013, 767 million people lived on less than $1.90 a day, down from 881 million in 2012 and 1.85 billion in 1990.

‘The percentage of developing world’s population living in poverty, unable to achieve education of find employment, continues to grow’.

Scholars, however, argue that the link between poverty and terrorism is not as direct as we think. In 2015, David Sterman wrote in ‘Don’t Dismiss Poverty’s Role in Terrorism Yet’ for Time: ‘Indeed, it is quite likely there are multiple routes into terrorism, some of which might involve poverty and some of which might not. When this data is aggregated, the poverty-related routes become less visible, but that does not mean they don’t exist.’ Sterman called for new research on the subject because ‘Assuming previous studies still explain the dynamics in the cases we face today could lead to blind spots allowing threats to mature unhindered.’

But in our modern connected world the indirect link can be stronger and is the cause of great concern. The negative influence and potentially damaging security symptoms of poverty in a particular region may be seen a long way away, as they are reported and form a key part of an extreme narrative to justify terrorist acts.

How might changing demographics make remaining protected more complicated?

Unfortunately, with the increased availability of technology and greater connectivity, the vulnerable individual may become involved in cyber-crime or exploited by those broadcasting radical views. The internet is a great tool for education however, it also gives access to views that deepen displeasure due to their lack of balance and individuals may be groomed as a security threat. Worth reading is this WhitePaper from Homeland Security on the threat of Internet Radicalization and how the youth in particular is targeted; and what should be done about it.

The challenge for nations, organisations and security professionals has grown from physical threat, and minimising it, to a broader threat that includes technology and cyber based threats. Monitoring and potentially seeking to remove malicious or inflammatory content that seeks to influence negatively or shape the thoughts or actions of at risk groups, is critical and connected to mitigating physical threat. Where the threat may be cyber in nature and require a response in kind, this is may be manageable for organisations of scale, but outside of the capability of many organisations and even nations that are at risk.

The solution sought cannot be limited to the resultant security threat and the cause must get as much if not more focus, as the right approach will assist to mitigate against subsequent generations merely presenting the same threat. The UNESCO estimates 263 million children are not enrolled in school, 73.4 million people are aged between 15 and 24; and 9 out of 10 people aged between 10 and 24 live in less developed countries. Whilst the individuals that make up these statistics may not get to more than a basic level of literacy or numeracy, they may be the group most vulnerable to being shown how to operate an AK47 for catastrophic effect whether in crime or terrorism related activity.

Children at school in Lagos, Nigeria

Fartun Weli, a founder of a non-profit helping Somali women, was quoted in a Time article, saying that “Kids are being recruited. Yes, this is a fact. What are we going to do about it? We have to talk about the root causes that make Somali kids vulnerable … we have to make sure there are opportunities created for our community to exit poverty.”

So where should we focus corporate social responsibility, and could there be a way that this could assist corporate, national or even international security?

Not a conclusion, more a provocation for further debate.

Shifting demographics contribute to volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity and the impact will increase and decrease over time. It should be seen as an essential risk to be mitigated and not merely a desirable to address if we can, with the focus shifting between the cause and the symptoms over the short, medium and long-term.

To cover the risk from excluded communities, illegal immigration, radicalisation and against a backdrop of reduced national budgets, collaboration is key. To address the cause, education can and is being developed through tie-ups between international bodies, national governments, charitable trusts, private sector companies and philanthropic investment; likewise, the easing of poverty requires a multi-agency and many faceted approach, with both require good and coordinated governance.

For the symptoms that constitute the security threat the mitigation of risks starts with understanding them as they change and grow, ahead of considering gaps in defence and creating the strategy to address them. The broadest team in that consideration will ensure all gaps are explored and covered, and that those seeking to mitigate the risk stay one step ahead of the threat.

Security is about managing the essential and the desirable, and whilst not a time for panic it is not a time for complacency either. Leadership that dynamically manages the security threat and pulls together the most suitable and combined response is key.

In response to the feedback of our client base and the impact of the increasing complexity that faces international businesses and other organisations, we have created Chelsea Group Security and Crisis Management. This brings together the long-standing capabilities of Hart Security Limited, specialist in the delivery of innovative, integrated security solutions in complex areas and Security Exchange, specialist in the prevention, management and recovery from critical security incidents worldwide.

Rob Noble is the Executive Director of the Chelsea Group Security and Crisis Management Division.